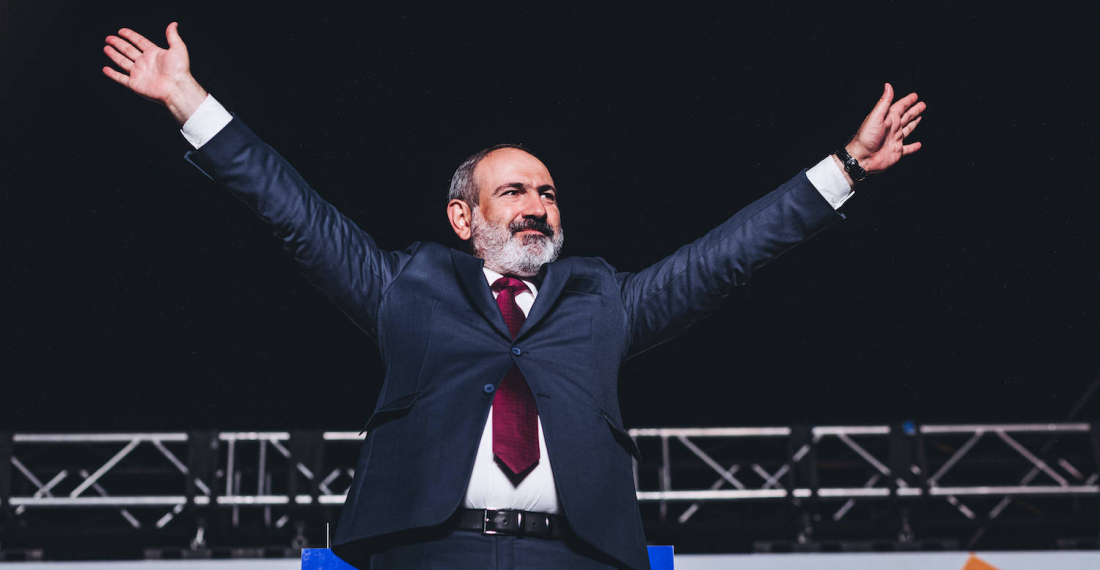

Whilst Nikol Pashinyan's victory in the recent Armenian elections is seen by some as a rejection of revanchist political forces, this does not mean there are no challenges to the peace process. Vasif Huseynov gives the perspective from Baku of what the elections mean for peace between Armenia and Azerbaijan in this op-ed for KarabakhSpace.eu.

The highly competitive snap parliamentary elections in Armenia on June 20, quite contrary to the expectations of many observers, ended with a landslide victory for the ruling Civil Contract party led by the acting prime minister, Nikol Pashinyan. Equally unexpectedly for many, the opposition quietly though reluctantly accepted this outcome and is planning to take the parliamentary seats it won. This situation was a great relief for the Armenian people who were worried about a potential civil war in the wake of the elections or the win of the discredited political figures like former presidents Robert Kocharyan and Serzh Sargsyan. Armenia is now hopeful for a better future with economic growth and democratic progress.

The defeat of the revanchist forces is widely interpreted by political analysts as Armenia’s public support to the post-war peace process between Armenia and Azerbaijan. These forces came together particularly under the umbrella of the Armenia Alliance bloc led by former president Robert Kocharyan who, deploying a fearmongering and bellicose strategy, was seeking to stir up nationalistic fervour in the country against the incumbent circles and promised to return some of the territories Azerbaijan liberated during the latest war. Although neither him nor any other opposition leader dared to reject the Russia-brokered ceasefire deal, he did not conceal his antipathy against the deal and subsequent peace negotiations.

Armenia has succeeded to overcome the threat of these dangerous groups taking over the leadership and endangering the peace negotiations with Azerbaijan. However, this does not mean that a smooth and unproblematic future awaits the peace process. While the post-elections period is widely seen as an opportunity towards this end, risks and challenges should not be overlooked.

Baku has long lamented that Armenia’s domestic political instability and social polarisation put obstacles to the peace process between the two countries. Azerbaijani leaders have on many occasions over the last few months declared their readiness to sign a peace treaty with Armenia and put a resolute end to all hostilities and conflicts. These calls have, however, not been reciprocated by the Armenian side. As President Ilham Aliyev of Azerbaijan noted in his meeting with the EU delegation on June 25, the government of Nikol Pashinyan has yet to respond to the peace treaty initiative of Azerbaijan. “If there is no peace treaty, it means there is no peace”, said Aliyev.

Revelations by some Armenian politicians in the aftermath of the elections demonstrate that there are actually political forces, not only in the opposition, but also in the highest echelons of the Armenian government, who seek to torpedo this peace process and avert any peaceful breakthrough with Azerbaijan. For example, the Armenian Security Council Secretary, Armen Grigoryan, recently disclosed that the former foreign minister, Ara Ayvazyan, denying the existence of minefield maps, had even prevented the rapid resolution of the issue of Armenian saboteurs detained after the Karabakh peace deal signed in November 2020. The sides reached an agreement over these issues quickly after Ayvazyan’s resignation on May 27.

The two countries, following the parliamentary elections, prepare to resume talks on the re-opening of regional transportation and communication channels as well as on the humanitarian issues (ie the return of Armenian detainees and the handover of minefield maps to Azerbaijan). They are also planning to restart the talks within the Armenian-Azerbaijani-Russian working group, which was established during the January 11 trilateral leaders’ summit and tasked with presenting action plans (including implementation schedules) to their governments regarding regional railroad and highway projects. In early June, the Armenian co-chair of the working group had declared that the group suspended its work due to the lack of “an appropriate environment” for effective work after the border dispute between Armenia and Azerbaijan in mid-May.

A few days after the elections, an optimistic statement concerning the future of these talks was made by Azerbaijan’s deputy prime minister, Shahin Mustafayev, the Azerbaijani co-chair of the trilateral working group. “I think that after the formation of a new government, the trilateral working group will continue its activity”, he said, adding that, “Until now, a constructive approach was observed at the meetings."

Despite this optimism, there are also risks associated with the results of Armenia’s parliamentary elections. A major risk is related with the polarisation of Armenian society and the threat it poses to the stability of the country. One Armenian analyst has rightly noted that the elections have brought this polarisation – which dramatically increased before the elections – to the parliament, as revanchist forces have won parliamentary seats and can now more assertively impact the policies of the government. Fragile public support to the new government might prevent Pashinyan’s cabinet resolutely countering these forces. This has the potential to unbalance Armenian politics, generate new political crises and, as such, prevent consistent foreign policies in a way akin to the pre-election period.

Another threat is related with the true nature of the electoral support to Nikol Pashinyan and his domestic and foreign policies. He might not be a revanchist like most of his political rivals, but he is arguably much more populist than any other political leader the post-Soviet Armenia has ever had. It is important to recall that it was his populist and reckless foreign policy moves that had derailed the peace negotiations and led to the tragic war in the fall of 2020. Azerbaijan is therefore worried whether Pashinyan’s new term will be loyal to the Russia-mediated trilateral agreements and the initiatives for state border delimitation and eventual peace treaty.

These concerns are also reinforced by the fact that although Pashinyan’s voters rejected the revanchist agenda of Robert Kocharyan, they, while voting, did not apparently prioritise the normalisation of relations with Azerbaijan and Turkey. Otherwise, they would have voted for Levon Ter-Petrosian, a former Armenian president and a candidate in the latest elections, who campaigned for peace in relations with neighbours. For Armenian voters, domestic socio-economic challenges of the country and the threat of former oligarchic regimes taking over the leadership turned out to be more important than the peace calls of Ter-Petrosian or revanchist agendas of Kocharyan.

On the one hand, this is a promising factor, as it is clear to Pashinyan’s government that Armenia cannot develop economically, unless it achieves peace with Azerbaijan and unblocks its transportation links. On the other hand, this holds some degree of uncertainty whether the new government will be constructively engaged with the peace process and succeed to stave off the destructive interventions of the revanchist groups which are now also in the parliament.